What Were the Rebels Fighting Agains in Sierra Leone

| Sierra Leone Civil State of war | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

Supported by: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| | | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| | | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 50,000[15] to 70,000[16] casualties 2.5 million displaced internally and externally[fifteen] | |||||||

The Sierra Leone Civil State of war (1991–2002), or the Sierra Leonean Ceremonious State of war, was a civil war in Sierra Leone that began on 23 March 1991 when the Revolutionary United Front (RUF), with support from the special forces of Charles Taylor'south National Patriotic Front of Liberia (NPFL), intervened in Sierra Leone in an attempt to overthrow the Joseph Momoh government. The resulting civil war lasted 11 years, enveloped the country, and left over l,000 dead.[15]

During the first year of the state of war, the RUF took control of large swathes of territory in eastern and southern Sierra Leone, which were rich in alluvial diamonds. The government's ineffective response to the RUF, and the disruption in regime diamond product, precipitated a military insurrection d'état in April 1992 past the National Conditional Ruling Council (NPRC).[17] By the finish of 1993, the Sierra Leone Regular army (SLA) had succeeded in pushing the RUF rebels back to the Liberian edge, but the RUF recovered and fighting connected. In March 1995, Executive Outcomes (EO), a Due south Africa-based individual military visitor, was hired to repel the RUF. Sierra Leone installed an elected noncombatant government in March 1996, and the retreating RUF signed the Abidjan Peace Accord. Under Un pressure level, the government terminated its contract with EO before the accord could exist implemented, and hostilities recommenced.[xviii] [nineteen]

In May 1997, a group of disgruntled SLA officers staged a coup and established the Armed Forces Revolutionary Council (AFRC) every bit the new government of Sierra Leone.[xx] The RUF joined with the AFRC to capture Freetown with lilliputian resistance. The new government, led by Johnny Paul Koroma, declared the war over. A moving ridge of looting, rape, and murder followed the announcement.[1] Reflecting international dismay at the overturning of the civilian government, ECOMOG forces intervened and retook Freetown on behalf of the government, but they found the outlying regions more hard to pacify.

In January 1999, world leaders intervened diplomatically to promote negotiations between the RUF and the government.[21] The Lome Peace Accord, signed on 27 March 1999, was the upshot. Lome gave Foday Sankoh, the commander of the RUF, the vice presidency and control of Sierra Leone'south diamond mines in render for a cessation of the fighting and the deployment of a United nations peacekeeping strength to monitor the disarmament process. RUF compliance with the disarmament procedure was inconsistent and sluggish, and by May 2000, the rebels were advancing again upon Freetown.[22]

Equally the Un mission began to neglect, the U.k. alleged its intention to intervene in the quondam colony and Commonwealth member in an attempt to back up the weak authorities of President Ahmad Tejan Kabbah. With assistance from a renewed United nations mandate and Guinean air support, the British Operation Palliser finally defeated the RUF, taking control of Freetown. On 18 January 2002, President Kabbah declared the Sierra Leone Civil War over.

Causes of the war [edit]

Political history [edit]

In 1961, Sierra Leone gained its independence from the United Kingdom. In the years following the expiry of Sierra Leone'due south first prime government minister Sir Milton Margai in 1964, politics in the state were increasingly characterized past abuse, mismanagement, and electoral violence that led to a weak civil order, the plummet of the education organization, and, by 1991, an entire generation of dissatisfied youth were attracted to the rebellious bulletin of the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) and joined the organization.[23] [24] Albert Margai, unlike his half-brother Milton, did not encounter the state every bit a steward of the public, merely instead as a tool for personal gain and self-aggrandizement and even used the armed services to suppress multi-party elections that threatened to terminate his rule.[25]

When Siaka Stevens entered politics in 1968, Sierra Leone was a constitutional republic. When he stepped down, seventeen years later, Sierra Leone was a one-party state.[26] Stevens' rule, sometimes chosen "the 17 year plague of locusts",[27] saw the devastation and perversion of every state institution. Parliament was undermined, judges were bribed, and the treasury was bankrupted to finance pet projects that supported insiders.[28] When Stevens failed to co-opt his opponents, he often resorted to state sanctioned executions or exile.[29]

In 1985, Stevens stepped down, and handed the nation's preeminent position to Major Full general Joseph Momoh, a notoriously inept leader who maintained the status quo.[28] During his seven-year tenure, Momoh welcomed the spread of unchecked corruption and complete economic collapse. With the land unable to pay its civil servants, those drastic enough ransacked and looted government offices and belongings. Fifty-fifty in Freetown, important commodities like gasoline were deficient. Only the authorities hitting rock lesser when information technology could no longer pay schoolteachers and the education system collapsed. Since simply wealthy families could afford to pay private tutors, the bulk of Sierra Leone's youth during the late 1980s roamed the streets aimlessly.[xxx] Equally infrastructure and public ethics deteriorated in tandem, much of Sierra Leone's professional grade fled the country. By 1991, Sierra Leone was ranked as ane of the poorest countries in the world, even though information technology benefited from ample natural resources including diamonds, gilded, bauxite, rutile, fe ore, fish, java, and cocoa.[31] [32]

Diamonds and the "resources curse" [edit]

The Eastern and Southern districts in Sierra Leone, well-nigh notably the Kono and Kenema districts, are rich in alluvial diamonds, and more chiefly, are easily accessible past anyone with a shovel, sieve, and transport.[33] Since their discovery in the early 1930s, diamonds take been critical in financing the continuing pattern of corruption and personal inflation at the expense of needed public services, institutions, and infrastructure.[34] The phenomenon whereby countries with an abundance of natural resource tend to nevertheless be characterized by lower levels of economic development is known every bit the "resource expletive".[35]

The presence of diamonds in Sierra Leone invited and led to the civil war in several ways. First, the highly unequal benefits resulting from diamond mining made ordinary Sierra Leoneans frustrated. Under the Stevens government, revenues from the National Diamond Mining Corporation (known as DIMINCO) – a joint government/DeBeers venture – were used for the personal enrichment of Stevens and of members of the government and concern elite who were close to him.[36] [37] When DeBeers pulled out of the venture in 1984, the government lost direct command of the diamond mining areas. By the late 1980s, almost all of Sierra Leone's diamonds were being smuggled and traded illicitly, with revenues going direct into the hands of private investors.[38] [39] In this menstruum the diamond trade was dominated past Lebanese traders and later (after a shift in favor on the part of the Momoh government) by Israelis with connections to the international diamond markets in Antwerp.[40] Momoh made some efforts to reduce smuggling and abuse in the diamond mining sector, only he lacked the political clout to enforce the law.[36] Even after the National Conditional Ruling Quango (NPRC) took ability in 1992, ostensibly with the goal of reducing corruption and returning revenues to the land, high-ranking members of the government sold diamonds for their personal proceeds and lived extravagantly off the proceeds.[41]

Diamonds also helped to arm the RUF rebels who used funds harvested from the alluvial diamond mines to buy weapons and ammunition from neighbouring Guinea, Liberia, and even SLA soldiers.[42] Merely the near significant connection betwixt diamonds and state of war is that the presence of easily extractable diamonds provided an incentive for violence.[43] To maintain control of important mining districts like Kono, thousands of civilians were expelled and kept away from these important economic centers.[44]

Although diamonds were a significant motivating and sustaining factor, there were other ways of profiting from the Sierra Leone Civil State of war. For instance, gold mining was prominent in some regions. Even more common was cash ingather farming through the utilise of forced labor. Looting during the Sierra Leone Civil War did not only center on diamonds, but as well included that of currency, household items, food, livestock, cars, and international aid shipments. For Sierra Leoneans who did not have admission to arable land, joining the insubordinate cause was an opportunity to seize property through the employ of deadly forcefulness.[45] But the virtually important reason why the civil state of war should not be entirely attributed to conflict over the economic benefits incurred from the alluvial diamond mines is that the pre-state of war frustrations and grievances did non just concern that of the diamond sector. More than twenty years of poor governance, poverty, corruption and oppression created the circumstances for the ascension of the RUF, every bit ordinary people yearned for change.[46]

The demographics of rebel recruitment [edit]

As a result of the Beginning Liberian Civil War, 80,000 refugees fled neighboring Liberia for the Sierra Leone – Liberian edge. This displaced population, composed almost entirely of children, would testify to be an invaluable nugget to the invading insubordinate armies because the refugee and detention centers, populated first past displaced Liberians and later by Sierra Leoneans, helped provide the manpower for the RUF's insurgency.[47] The RUF took advantage of the refugees, who were abandoned, starving, and in dire need of medical attention, by promising food, shelter, medical care, and looting and mining profits in return for their support.[48] When this method of recruitment failed, every bit it oftentimes did for the RUF, youths were often coerced at the butt of a gun to join the ranks of the RUF. Later being forced to join, many child soldiers learned that the complete lack of law – as a effect of the civil war – provided a unique opportunity for self-empowerment through violence and thus continued to support the rebel crusade.[49]

Libyan and arms dealing role [edit]

Muammar al-Gaddafi both trained and supported Charles Taylor.[50] Gaddafi also helped Foday Sankoh, the founder of Revolutionary United Front.[51]

Russian businessman Viktor Tour supplied Charles Taylor with artillery for apply in Sierra Leone and had meetings with him about the operations.[52]

The war [edit]

SLA response; Sobels [edit]

SLA soldiers and advisers

The initial rebellion could have easily been quelled in the outset half of 1991. But the RUF – despite beingness both numerically inferior and extremely roughshod confronting civilians – controlled a pregnant portion of the state by the year'southward end. The SLA's equally poor behavior fabricated this event possible.[33] Often agape to direct confront or unable to locate the elusive RUF, government soldiers were cruel and indiscriminate in their search for rebels or sympathizers amongst the civilian population. After retaking captured towns, the SLA would perform a 'mopping up' operation in which the towns people were transported to concentration military camp styled 'strategic hamlets' far from their homes in Eastern and Southern Sierra Leone under the pretense of separating the population from the insurgents. Withal, in many cases, this was followed by much looting and theft afterward the villagers were evacuated.[53]

The SLA's sordid beliefs inevitably led to the alienation of many civilians and pushed some Sierra Leoneans to join the rebel cause. With morale depression and rations even lower, many SLA soldiers discovered that they could practice better by joining with the rebels in looting civilians in the countryside instead of fighting confronting them.[1] The local civilians referred to these soldiers equally 'sobels' or 'soldiers by day, rebels past dark' because of their close ties to the RUF. Past mid-1993, the two opposing sides became virtually indistinguishable. For these reasons, civilians increasingly relied on an irregular force chosen the Kamajors for their protection.[54]

Ascension of the Kamajors [edit]

A grassroots militia forcefulness, the Kamajors operated invisibly in familiar territory and was a significant impediment to marauding government and RUF troops.[55] [56] For displaced and unprotected Sierra Leonans, joining the Kamajors was a ways of taking up arms to defend family and abode due to the SLA'due south perceived incompetence and active bunco with the rebel enemy. The Kamajors clashed with both government and RUF forces and was instrumental in countering regime soldiers and rebels who were looting villages.[57] The success of the Kamajors raised calls for its expansion, and members of street gangs and deserters were also co-opted into the organization. However, the Kamajors became corrupt and deeply involved in extortion, murder, and kidnappings past the end of the conflict.[58]

National Provisional Ruling Council [edit]

Within ane year of fighting, the RUF offensive had stalled, simply information technology even so remained in control of large territories in Eastern and Southern Sierra Leone leaving many villages unprotected while as well disrupting food and authorities diamond production. Shortly the regime was unable to pay both its civil servants and the SLA. As a issue, the Momoh authorities lost all remaining brownie and a group of disgruntled junior officers led by Helm Valentine Strasser overthrew Momoh on 29 April 1992.[17] [59] Strasser justified the coup and the establishment of the National Provisional Ruling Council (NPRC) by referencing the corrupt Momoh regime and its inability to resuscitate the economy, provide for the people of Sierra Leone, and repel the rebel invaders. The NPRC's coup was largely popular considering information technology promised to bring peace to Sierra Leone.[threescore] But the NPRC'south promise would bear witness to be short lived.[61]

In March 1993, with much assistance from ECOMOG troops provided past Nigeria, the SLA recaptured the Koidu and Kono diamond districts and pushed the RUF to the Sierra Leone – Liberia border.[62] The RUF was facing supply issues every bit the United Liberation Motility of Republic of liberia for Republic (ULIMO) gains inside Liberia were restricting the ability of Charles Taylor's NPFL to merchandise with the RUF. By the stop of 1993, many observers idea that the war was over considering for the first time in the conflict the Sierra Leone Army was able to found itself in the Eastern and the Southern mining districts.[63]

Nevertheless, with senior government officials neglectful of the weather condition faced by SLA soldiers, front line soldiers became resentful of their poor conditions and began helping themselves to Sierra Leone'southward rich natural resources.[64] This included alluvial diamonds equally well as looting and 'sell game', a tactic in which government forces would withdraw from a town but non earlier leaving arms and ammunition for the roving rebels in return for greenbacks.[33] Renegade SLA soldiers even clashed with Kamajor units on a number of occasions when the Kamajors intervened to halt the looting and mining. The NPRC government also had a motivation for allowing the war to continue, since every bit long as the country was at state of war the military government would not exist called upon to mitt over dominion to a democratically elected civilian authorities.[63] The war dragged on equally a low intensity conflict until Jan 1995 when RUF forces and dissident SLA elements seized the SIEROMCO (bauxite) and Sierra Rutile (titanium dioxide) mines in the Moyamba and Bonthe districts in the country'due south south west, furthering the authorities'southward economical struggles and enabling a renewed RUF advance on the upper-case letter at Freetown.[65]

Executive Outcomes [edit]

In March 1995, with the RUF within twenty miles of Freetown, Executive Outcomes, a individual war machine company from Southward Africa, arrived in Sierra Leone. The government paid EO $1.viii million per month (financed primarily by the International Monetary Fund),[66] to achieve three goals: return the diamond and mineral mines to the government, locate and destroy the RUF's headquarters, and operate a successful propaganda program that would encourage local Sierra Leoneans to support the government of Sierra Leone.[23] EO's military machine force consisted of 500 armed services directorate and three,000 highly trained and well-equipped combat-set soldiers, backed by tactical air support and send. Executive Outcomes employed black Angolans and Namibians from apartheid-era South Africa's former 32 Battalion, with an officer corps of white South Africans.[67] Harper'south Mag described this controversial unit every bit a collection of former spies, assassins, and crack bush guerrillas, most of whom had served for fifteen to twenty years in South Africa'south nigh notorious counter insurgency units.[68]

As a military force, EO was remarkably effective and conducted a highly successful counter insurgency against the RUF. In just ten days of fighting, EO was able to drive the RUF forces dorsum sixty miles into the interior of the country.[67] EO outmatched the RUF forces in all operations. In just seven months, EO, with back up from loyal SLA and the Kamajors battalions, recaptured the diamond mining districts and the Kangari Hills, a major RUF stronghold.[69] A second offensive captured the provincial capital letter and the largest city in Sierra Leone and destroyed the RUF's master base of operations near Bo, finally forcing the RUF to admit defeat and sign the Abidjan Peace Accordance in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire on 30 November 1996.[70] This catamenia of relative peace also immune the land to hold parliamentary and presidential elections in February and March 1996.[71] Ahmad Tejan Kabbah (of the Sierra Leone People's Political party [SLPP]), a diplomat who had worked at the UN for more than twenty years, won the presidential election.[72]

Abidjan Peace Accord [edit]

The Abidjan Peace Accord mandated that Executive Outcomes was to pull out within five weeks after the arrival of a neutral peacekeeping forcefulness. The principal stumbling block that prevented Sankoh from signing the understanding sooner was the number and type of peacekeepers that were to monitor the ceasefire.[21] [73] Additionally, connected Kamajor attacks and the fear of castigating tribunals following demobilization kept many rebels in the bush-league despite their dire situation. However, in Jan 1997, the Kabbah government – beset by demands to reduce expenditures by the International Monetary Fund – ordered EO to get out the country, even though a neutral monitoring force had withal to go far.[19] [70] The departure of EO opened up an opportunity for the RUF to regroup for renewed military attacks.[nineteen] The March 1997 arrest of RUF leader Foday Sankoh in Nigeria also angered RUF members, who reacted with escalated violence. Past the end of March 1997, the peace accordance had collapsed.[74]

AFRC/RUF coup and interregnum [edit]

After the departure of Executive Outcomes, the credibility of the Kabbah authorities declined, especially among members of the SLA, who saw themselves being eclipsed by both the RUF on one side and the independent but pro-regime Kamajors on the other.[75] On 25 May 1997, a grouping of disgruntled SLA officers freed and armed 600 prisoners from the Pademba Road prison in Freetown. One of the prisoners, Major Johnny Paul Koroma, emerged as the leader of the coup and the War machine Revolutionary Council (AFRC) proclaimed itself the new authorities of Sierra Leone.[xx] After receiving the blessing of Foday Sankoh, who was and then living under house abort in Nigeria, members of the RUF – supposedly on its last legs – were ordered out of the bush to participate in the coup. Without hesitation and encountering only calorie-free resistance from SLA loyalists, 5,000 rag-tag rebel fighters marched 100 miles and overran the capital. Without fear or reluctance, RUF and SLA dissidents and so proceeded to parade peacefully together. Koroma then appealed to Nigeria for the release of Sankoh, appointing the absent-minded leader to the position of deputy chairman of the AFRC.[76] The joint AFRC/RUF leadership then proclaimed that the war had been won, and a great wave of looting and reprisals against civilians in Freetown (dubbed "Performance Pay Yourself" by some of its participants) followed.[77] [78] President Kabbah, surrounded simply by his bodyguards, left by helicopter for exile in nearby Guinea.[79]

The AFRC junta was opposed by members of Sierra Leone's ceremonious society such as student unions, journalists associations, women'south groups and others, not simply because of the violence information technology unleashed but because of its political attacks on press freedoms and civil rights.[fourscore] The international response to the coup was also overwhelmingly negative.[81] The UN and the Organization of African Unity (OAU) condemned the coup, foreign governments withdrew their diplomats and missions (and in some cases evacuated civilians) from Freetown, and Sierra Leone's membership in the Commonwealth was suspended.[82] The Economic Community of Westward African States (ECOWAS) also condemned the AFRC insurrection and demanded that the new junta return power peacefully to the Kabbah government or risk sanctions and increased military presence by ECOMOG forces.[83] [84]

ECOMOG's intervention in Sierra Leone brought the AFRC/RUF rebels to the negotiating table where, in October 1997, they agreed to a tentative peace known every bit the Conakry Peace Plan.[85] Despite having agreed to the plan, the AFRC/RUF continued to fight. In March 1998, overcoming entrenched AFRC positions, the ECOMOG forces retook the capital and reinstated the Kabbah government, but permit the rebels flee without further harassment.[86] [87] The regions lying only beyond Freetown proved much more than difficult to pacify. Cheers in part to bad road conditions, lack of back up aircraft, and a revenge driven insubordinate force, ECOMOG'south offensive ground to a halt just outside Freetown. ECOMOG'southward forces suffered from several weakness, the most important existence, poor control and control, low morale, poor training in counterinsurgency, depression manpower, limited air and body of water capability, and poor funding.[88]

Unable to consistently defend itself confronting the AFRC/RUF rebels, the Kabbah regime was forced to make serious concessions in the Lome Peace Agreement of July 1999.[89]

Lome peace understanding [edit]

Given that Nigeria was due to recall its ECOMOG forces without achieving a tactical victory over the RUF, the international customs intervened diplomatically to promote negotiations between the AFRC/RUF rebels and the Kabbah authorities.[xc] The Lome Peace Accordance, signed on 7 July 1999, is controversial in that Sankoh was pardoned for treason, granted the position of Vice President, and fabricated chairman of the commission that oversaw Sierra Leone'south diamond mines.[91] In return, the RUF was ordered to demobilize and disarm its armies under the supervision of an international peacekeeping strength which would initially be nether the authority of both ECOMOG and the United nations. The Lome Peace Agreement was the subject of protests both in Sierra Leone and by international human rights groups abroad, mainly because it handed over to Sankoh, the commander of the brutal RUF, the second near powerful position in the country, and control over all of Sierra Leone's lucrative diamond mines.[91]

DDR process [edit]

Post-obit the Lome Peace Agreement, the security state of affairs in Sierra Leone was all the same unstable considering many rebels refused to commit themselves to the peace process.[21] [92] The Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration camps were an attempt to convince the insubordinate forces to literally exchange their weapons for food, article of clothing, and shelter.[93] During a six-week quarantine menses, onetime combatants were taught basic skills that could be put to use in a peaceful profession after they return to lodge. After 2001, DDR camps became increasingly constructive and by 2002 they had collected over 45,000 weapons and hosted over 70,000 former combatants.[94]

UNAMSIL intervention [edit]

In October 1999 the United nations established the United nations Mission to Sierra Leone (UNAMSIL). The main objective of UNAMSIL was to assist with the disarmament process and enforce the terms established under the Lome Peace Agreement.[21] Unlike other previous neutral peacekeeping forces, UNAMSIL brought serious military ability.[95] The original multi-national force was commanded by General Vijay Jetley of India.[96] Jetley afterwards resigned and was replaced by Lieutenant General Daniel Opande of Kenya in November 2000.[97] Jetley had accused Nigerian political and armed services officials at the elevation of the Un mission of "sabotaging peace" in favor of national interests, and alleged that Nigerian army commanders illegally mined diamonds in league with RUF.[98] The Nigerian ground forces called for General Jetley'south resignation immediately after the report was released, maxim they could no longer work with him.[98]

UNAMSIL forces began arriving in Sierra Leone in December 1999. At that time the maximum number of troops to exist deployed was fix at 6,000. Only a few months later, though, in February 2000, a new Un resolution authorized the deployment of 11,000 combatants.[99] In March 2001 that number was increased to 17,500 troops, making it at the time the largest United nations force in beingness,[97] and UNAMSIL soldiers were deployed in the RUF-held diamond areas. Despite these numbers, UNAMSIL was frequently rebuffed and humiliated by RUF rebels, being subjected to attacks, obstruction and disarmament. In the almost egregious instance, in May 2000 over 500 UNAMSIL peacekeepers were captured by the RUF and held earnest. Using the weapons and armored personnel carriers of the captured UNAMSIL troops, the rebels advanced towards Freetown, taking over the town of Lunsar to its northeast.[22] For over a year afterwards, the UNAMSIL strength meticulously avoided intervening in RUF controlled mining districts lest another major incident occur.[100] Subsequently the UNAMSIL force had substantially rearmed the RUF, a call for a new military intervention was made to relieve the UNAMSIL hostages and the government of Sierra Leone.[95] Subsequently Operation Palliser and Operation Khukri the situation stabilized and UNAMSIL gain command.

In late 1999, the Un Security Council asked Russian federation for participation in a peacekeeping mission in Sierra Leone. The Federation Council of Russian federation decided to send iv Mil Mi-24 assault helicopters with 115 crew and technical personnel into Sierra Leone. Many of them had combat experience in Transitional islamic state of afghanistan and Chechnya. The destroyed Lungi ceremonious airfield in the suburbs of Freetown became their base of operations. A Ukrainian Detached Recovery and Restoring Battalion, and aviation team were stationed near Freetown. The two post-Soviet troop contingents got along well, and left together after the UN mandate for peacekeeping operations ended in June 2005.[101] [ unreliable source? ]

Functioning Khukri [edit]

Operation Khukri was a unique multinational performance launched in the United Nations Assistance Mission in Sierra Leone (UNAMSIL), involving India, Nepal, Ghana, Great britain and Nigeria. The aim of the operation was to interruption the ii-month-long siege laid by armed cadres of the RUF around 2 companies of 5/8 Gorkha Rifles (GR) Infantry Battalion Group at Kailahun by affecting a fighting intermission out and redeploying them with the main battalion at Daru.[102] About 120 special forces operators commanded by Major (at present Lt. Col.) Harinder Sood were airlifted from New Delhi to spearhead the mission to rescue 223 men of the Gorkha Rifles who were surrounded and besieged by the RUF rebels for over 75 days. The mission was a total success which resulted in safe rescue of all the besieged men and inflicted several hundreds of casualties on the RUF, where Indian troops were part of a multinational UN peacekeeping force.[103] [104]

British intervention [edit]

A British Sea Harrier jet, such every bit those used to back up government forces

In May 2000, the situation on the ground had deteriorated to such an extent that British paratroopers were deployed in Operation Palliser to evacuate foreign nationals and establish order.[105] They stabilized the situation, and were the catalyst for a ceasefire that helped stop the state of war. The British forces, nether the command of Brigadier David Richards, expanded their original mandate, which was limited to evacuating commonwealth citizens, and now aimed to salvage UNAMSIL from the brink of collapse. At the fourth dimension of the British intervention in May 2000, half of the country remained under the RUF's command. The one,200 homo British ground force – supported by air and ocean power – shifted the balance of power in favor of the government and the rebel forces were easily repelled from the areas beyond Freetown.[106]

Terminate of the war [edit]

Several factors led to the end of the civil war. First, Guinean cross-border bombing raids against villages believed to be bases used by the RUF working in conjunction with Guinean dissidents were very effective in routing the rebels.[107] [108] Another cistron encouraging a less antagonistic RUF was a new UN resolution that demanded that the regime of Liberia miscarry all RUF members, finish their financial back up of the RUF, and halt the illicit diamond merchandise.[109] Finally, the Kamajors, feeling less threatened now that the RUF was disintegrating in the face of a robust opponent, failed to incite violence similar they had washed in the past. With their backs confronting the wall and without whatever international support, the RUF forces signed a new peace treaty inside a thing of weeks.

On xviii January 2002, President Kabbah declared the eleven-year-long Sierra Leone Civil War officially over.[110] By nigh estimates, over l,000 people had lost their lives during the war.[xv] [111] Countless more vicious victim to the reprehensible and perverse behavior of the combatants. In May 2002 President Kabbah and his SLPP, won landslide victories in the presidential and legislative elections. Kabbah was re-elected for a 5-year term. The RUF'due south political wing, the Revolutionary United Front Political party (RUFP), failed to win a single seat in parliament. The elections were marked by irregularities and allegations of fraud, only non to a caste that significantly afflicted the event.[112]

War atrocities and crimes confronting humanity [edit]

A schoolhouse destroyed during the ceremonious war, in Kono, eastern Sierra Leone.

During the Sierra Leone Civil War numerous atrocities were committed including war rape, mutilation, and mass murder, causing many of the perpetrators to be tried in international criminal courts, and the establishment of a truth and reconciliation commission. A 2001 overview noted that at that place had been "serious and grotesque man rights violations" in Sierra Leone since its ceremonious war began in 1991. The rebels, the Revolutionary United Front (RUF), had "committed horrendous abuses". The report noted that "25 times as many people" had already been killed in Sierra Leone than had been killed in Kosovo at the point when the international community decided to accept action. "In fact, information technology has been pointed out past many that the atrocities in Sierra Leone have been worse than was seen in Kosovo."[113] destroyed by RUF insubordinate forces. In total, 1,270 master schools were destroyed in the War.[114] These crimes included merely are not express to:

List of crimes [edit]

- Mass killings of civilians – The most notorious mass killing was the 1999 Freetown massacre. This took place in January 1999 when the AFRC/RUF set upon Freetown in a bloody assail known as "Operation No Living Thing" in which rebels entered neighborhoods to loot, rape and impale indiscriminately.[115] A Human Rights Watch report[116] documented the atrocities committed during this attack. The written report estimated that over 7,000 people were killed and that at least half of them were civilians.[117] Reports from survivors describe perverse brutality including incinerating people alive while locked in their houses, hacking civilians' easily and other limbs off with machetes and fifty-fifty eating them.[118]

- Drafting of underage soldiers – Nigh one quarter of the soldiers serving in the government armed services during the civil war were under age xviii.[113] "Recruitment methods were savage – sometimes children were abducted, sometimes they were forced to impale members of their own families so every bit to brand them outcasts, sometimes they were drugged, sometimes they were forced into conscription by threatening family unit members." Child soldiers were deliberately overwhelmed with violence "in social club to completely desensitize them and brand them mindless killing machines".[119] [120]

- Mass state of war rape – During the state of war gender specific violence was widespread. Rape,[121] sexual slavery and forced marriages were commonplace during the disharmonize.[122] The majority of assaults were carried out past the Revolutionary United Front end (RUF). The Armed services Revolutionary Council (AFRC), The Civil Defense force Forces (CDF), and the Sierra Leone Army (SLA) have likewise been implicated in sexual violence. The RUF, even though they had access to women, who had been abducted for use as either sexual practice slaves or combatants, ofttimes raped non-combatants.[123] The militia also carved the RUF initials into women'southward bodies, which placed them at risk of beingness mistaken for enemy combatants if they were captured by government forces.[124] Women who were in the RUF were expected to provide sexual services to the male person members of the militia. And of all women interviewed, but two had not been repeatedly subjected to sexual violence; gang rape and individual rapes were commonplace.[125] A study from PHR stated that the RUF was guilty of 93 per cent of sexual assaults during the conflict.[126] The RUF was notorious for homo rights violations, and regularly amputated artillery and legs from their victims.[127] Trafficking by military and militias of women and girls, for use equally sexual activity slaves is well documented, with reports from recent conflicts such as those in Angola, the former Yugoslavia, Sierra Leone, Republic of liberia, the DRC, Indonesia, Colombia, Burma and Sudan.[128] During the decade long civil conflict in Sierra Leone, women were used as sexual practice slaves having been trafficked into refugee camps. Co-ordinate to PHR, 1 third of women who reported sexual violence had been kidnapped, with fifteen per cent forced into sexual slavery. The PHR written report likewise showed that ninety iv per cent of internally displaced households had been victims of some form of violence.[129] PHR estimated that there were between 215,000 and 257,000 victims of rape during the conflict.[130] [131] [132]

Cry Freetown the 2000 documentary film directed past Sorious Samura shows accounts of the victims of the Sierra Leone Civil War and depicts the near brutal period with the Revolutionary United Front end (RUF) rebels called-for houses and The ECOMOG soldiers summarily executing suspects. Sorious Samura films Nigerian soldiers executing suspects without trial including women and children.[133]

After the state of war [edit]

Withdrawal [edit]

President Kabbah meeting with Prime number Minister Mohammad Mosaddak Ali at his Part in Dhaka, Bangladesh in 2004. People's republic of bangladesh, together with many other countries, played a key role in the Un's mission in Sierra Leone (UNAMSIL).

On 28 July 2002 the British withdrew a 200-stiff military machine contingent that had been in country since the summer of 2000, leaving behind a 140-strong military training team with orders to professionalize the SLA and Navy. In November 2002, UNAMSIL began a gradual reduction from a peak level of 17,800 personnel.[134] Under pressure level from the British, the withdrawal slowed, so that by October 2003 the UNAMSIL contingent all the same stood at 12,000 men. As peaceful atmospheric condition continued through 2004, yet, UNAMSIL drew downwardly its forces to slightly over 4,100 by December 2004. The United nations Security Council extended UNAMSIL's mandate until June 2005 and once again until December 2005. UNAMSIL completed the withdrawal of all troops in Dec 2005 and was succeeded past the United Nations Integrated Office in Sierra Leone (UNIOSIL).[135]

Truth and Reconciliation Commission [edit]

The Lome Peace Accord called for the establishment of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission to provide a forum for both victims and perpetrators of human rights violations during the disharmonize to tell their stories and facilitate healing. Subsequently, the Sierra Leonean authorities asked the Un to help set upward a Special Court for Sierra Leone, which would endeavour those who "conduct the greatest responsibility for the commission of crimes confronting humanity, state of war crimes and serious violations of international humanitarian law, as well as crimes under relevant Sierra Leonean law within the territory of Sierra Leone since 30 November 1996." Both the Truth and Reconciliation Committee and the Special Courtroom began operating in the summertime of 2002.[136] [137]

Rehabilitation [edit]

Population [edit]

After the state of war many of the children who were abducted and used in the conflict needed some form of rehabilitation, debriefing and intendance later the conflict came to an end. Only a handful of the children could be immediately sent home afterwards six weeks of debriefing at a center for ex-combatants. This is due to many of the children suffering from drug withdraw symptoms, brainwashing, physical and mental wounds, besides as a lack of memory of who they were or where they came from before the conflict.[138]

There was an estimated 1 to two million displaced persons and refugees who wanted to or needed to exist returned to their villages.[139]

Rebuilding [edit]

Reportedly thousands of small villages had been severely damaged due to annexation, and targeted devastation of belongings that was held past perceived enemies. There was also heavy destruction of clinics and hospitals, leading to a concern about infrastructure stability.[139]

Government [edit]

The European Union [EU] sent budgetary back up with the support of the Imf, the World Bank and the U.k. in an effort to stabilize the economy and the government. The amount; €iv,75 million was made available by the EU from 2000 to 2001, for the government finance interalia, and social services.[139] Afterwards the contribution made by the People's republic of bangladesh UN Peacekeeping Force, the government of Ahmad Tejan Kabbah alleged Bengali an honorary official language in December 2002.[4] [five] [half-dozen] [seven]

Diamond revenues [edit]

Diamond revenues in Sierra Leone have increased more than than tenfold since the cease of the conflict, from $ten million in 2000 to nearly $130 million in 2004, although co-ordinate to the UNAMSIL surveys of mining sites, "more than 50 per cent of diamond mining even so remains unlicensed and reportedly considerable illegal smuggling of diamonds continues".[140]

Prosecution [edit]

Stephen J. Rapp, chief prosecutor

On 13 January 2003, a small grouping of armed men tried unsuccessfully to break into an armory in Freetown. Former AFRC-junta leader Koroma, after being linked to the raid, went into hiding. In March, the Special Court for Sierra Leone issued its start indictments for war crimes during the civil state of war. Sankoh, already in custody, was indicted, forth with notorious RUF field commander Sam "Mosquito" Bockarie, Koroma, the Minister of Interior and erstwhile caput of the Civil Defence force, Samuel Hinga Norman, and several others. Norman was arrested when the indictments were announced, while Bockarie and Koroma remained at big (presumably in Liberia). On 5 May 2003, Bockarie was killed in Liberia. President Taylor expected to be indicted by the Special Court and had feared Bockarie's testimony.[141] He is suspected of ordering Bockarie's murder, although no indictments are awaiting.[142]

Several weeks later, give-and-take filtered out of Republic of liberia that Koroma had been killed as well, although his expiry remains unconfirmed. In June the Special Court appear Taylor's indictment for state of war crimes.[143] Sankoh died in prison in Freetown on 29 July 2003 from a pulmonary embolism.[144] He had been ailing since a stroke the year prior.[145]

In August 2003 President Kabbah testified before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission on his office during the civil state of war. On one Dec 2003, Major General Tom Carew, who had been the Chief of Defence force Staff for the Regime of Sierra Leone and an important figure in the SLA, was reassigned to noncombatant duties. In June 2007, the Special Court found 3 of the xi people indicted – Alex Tamba Brima, Brima Bazzy Kamara and Santigie Borbor Kanu – guilty of war crimes, including acts of terrorism, commonage punishments, extermination, murder, rape, outrages upon personal dignity, conscripting or enlisting children under the age of 15 years into armed forces, enslavement and pillage.[146]

Depictions [edit]

In 2000, the Sierra Leonean journalist, cameraman and editor, Sorious Samura released his documentary Cry Freetown. The self-funded film depicted the most brutal period of the civil war in Sierra Leone with RUF rebels capturing the capital urban center in the late 1990s and the subsequent fight past ECOMOG and loyal government forces' to accept back control of the urban center. The moving picture won, amongst other awards, an Emmy Honor and a Peabody.

The documentary pic Sierra Leone's Refugee All Stars tells the story of a group of refugees who fled to Guinea and created a band to ease the hurting of the abiding difficulty of living abroad from dwelling house and customs after the atrocities of state of war and mutilation.[147]

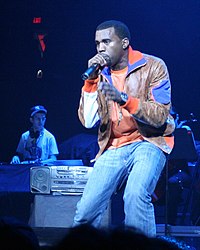

West performing at a concert in 2005, Portland, Usa - four months afterward the release of Late Registration

The title and lyrics of American rapper Kanye West's 2005 hit song Diamonds from Sierra Leone, from his 2nd studio anthology Tardily Registration, were based off one of the cardinal circumstances surrounding the civil war (conflict/blood diamonds). West was inspired to record the song later reading about the event of conflict diamonds and how their sales were continuing to fuel the violent civil war in Sierra Leone.[148] The song won All-time Rap Vocal at the 48th Annual Grammy Awards, and won one of the Pop Awards at the 2006 BMI London Awards, before existence named by Camber Mag as among the all-time singles of the 2000s decade.[149] [150]

The civil state of war too served every bit the background for the 2006 pic Claret Diamond, starring Leonardo DiCaprio, Djimon Hounsou and Jennifer Connelly.[151] During the end of the movie Lord of State of war, Yuri Orlov (played past Nicolas Cage) sells arms to militias during the civil war. The militias are allied with André Baptiste (Eamonn Walker), who is based on Charles Taylor.[152]

The apply of children in both the rebel (RUF) military and the regime militia is depicted in Ishmael Beah'southward 2007 memoir, A Long Fashion Gone.

Mariatu Kamara wrote about being attacked by the rebels and having her hands chopped off in her book The Bite of the Mango. Ishmael Beah wrote a foreword to Kamara's book.[153]

In the 2012 Documentary La vita not perde valore, by Wilma Massucco, sometime child soldiers and some of their victims talk near the way how they experience and live, 10 years afterwards the Sierra Leone civil war ending, thank you to the personal, familiar and social rehabilitation provided to them by Father Giuseppe Berton, an Italian missionary of the Xaverian order. The documentary has been analyzed in dissimilar Universities, condign discipline of various degrees,.[154] [155]

Jonathon Torgovnik wrote about eight women that he interviewed after the war had ended in his book; Girl Soldier: Life Afterwards War in Sierra Leone. In the book he describes the experiences of the eight women who were abducted during the state of war and forced to fight in it.[156]

See too [edit]

- Burundian Civil War

- 2nd Congo State of war

- 2nd Liberian Ceremonious War

References [edit]

- ^ a b c Gberie, p. 102

- ^ Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board, Canada (three September 1999) Sierra Leone: The Tamaboros and their role in the Sierra Leonian conflict. UNHCR. Retrieved xvi January 2022.

- ^ Торговля оружием и будущее Белоруссии

- ^ a b "How Bengali became an official linguistic communication in Sierra Leone". The Indian Limited. 21 Feb 2017. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ^ a b "Why Bangla is an official language in Sierra Leone". Dhaka Tribune. 23 February 2017.

- ^ a b Ahmed, Nazir (21 February 2017). "Recounting the sacrifices that made Bangla the Country Linguistic communication".

- ^ a b "Sierra Leone makes Bengali official language". Islamic republic of pakistan. 29 December 2002. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013.

- ^ "United nations Peace Keeping Missions: Sierra Leone (2001 – To Dec 2005)". pakistanarmy.gov.pk. Pakistan Army. Archived from the original on thirteen September 2017. Retrieved xiii September 2017.

- ^ "AFRICA | Peacekeepers feared killed". BBC News. 23 May 2000. Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- ^ "United kingdom | Britain's role in Sierra Leone". BBC News. 10 September 2000. Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- ^ Doyle, Mark. "Good day to the full general". Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ^ "Liberia: Sometime Insubordinate Commander Benjamin Yeaten Notwithstanding A Fugitive From Justice". African Orbit. eight June 2017. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ^ "UNAMSIL: Un Mission in Sierra Leone – Groundwork". Un.org . Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- ^ Iron, Richard (February 2019). Rapid Intervention and Conflict Resolution: British War machine Intervention in Sierra Leone 2000-2002. Australian Ground forces Research Centre. Retrieved 16 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d Gberie, p. 6

- ^ Kaldor, Mary; Vincent, James (2006). Evaluation of UNDP assistance to disharmonize-afflicted countries: Case Study: Sierra Leone (PDF). New York City: United Nations Development Plan. p. four. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ a b Gberie, p. 103

- ^ Keen, p. 111

- ^ a b c Abdullah, p. 118

- ^ a b Abdullah, p.180

- ^ a b c d Gberie, p. 161

- ^ a b Abdullah, pp. 214–17

- ^ a b Abdullah, p. 90

- ^ Abdullah, pp. 240–41

- ^ Gberie, p. 26

- ^ Gberie, p. 28

- ^ Ayittey, George B.N. "A New Mandate For UN Mission In Africa". CADS Global Network. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 24 December 2010.

- ^ a b Abdullah, p. 93

- ^ Pham, John-Peter (2005). Child Soldiers, Developed Interests: The Global Dimension of the Sierra Leonean Tragedy. New York: Nova Science Publishers. p. 45.

- ^ Gberie, p. 45

- ^ "Gross domestic product per capita (current Usa$)". The World Depository financial institution Information Catalog . Retrieved 29 Dec 2010.

- ^ "Sierra Leone". The Earth Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 29 Dec 2010.

- ^ a b c Abdullah, p. 106

- ^ Gberie, p. xviii

- ^ Auty, Richard Thousand. (1993). Sustaining Evolution in Mineral Economies: The Resources Curse Thesis. London: Routledge.

- ^ a b Keen, p. 23

- ^ Federico, Victoria (2007). "The Curse of Natural Resources and Human Development". L-SAW: Lehigh Student Accolade Winners. Archived from the original on 22 March 2012.

- ^ Bully, p. 22

- ^ Hirsch, pp. 27–28

- ^ Smillie, Ian, Gberie, Lansana and Hazelton, Ralph (January 2000). "The Heart of the Thing: Sierra Leone, Diamonds, and Insecurity (Summary Report)" (PDF). Ottawa, Ontario: Partnership Africa Canada: 5. CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Abdullah, p. 95

- ^ Abdullah, p. 100

- ^ Gberie, p. 184

- ^ Erbick, Stephen (2012). "Economization of the Sierra Leone State of war". twenty. Lehigh University: 10.

- ^ Gberie, p. 85

- ^ Abdullah, p. 99

- ^ Gberie, p. 56

- ^ Gberie, p. 59

- ^ Gberie, p. 151

- ^ "How the mighty are falling". The Economist. 5 July 2007. Retrieved 17 July 2007.

- ^ James Solar day (15 March 2011). "Revealed: Colonel Gaddafi's school for scoundrels". Metro.

- ^ Merchant of decease: coin, guns, planes, and the human being who makes war possible. Douglas Farah, Stephen Braun. p. 164

- ^ Gberie, p. 127

- ^ Abdullah, p. 4

- ^ Gberie, p. 110

- ^ "In Search of the Kamajors, Sierra Leone's Noncombatant Counter-insurgents". Crisis Group. 7 March 2017. Retrieved xix May 2021.

- ^ Abdullah, p. 168

- ^ Gberie, p. 134

- ^ Abdullah, p.105

- ^ Gberie, p. 72

- ^ Gberie, p. 74

- ^ Gberie, p. 65

- ^ a b Abdullah, p. 108

- ^ Gberie, p. 180

- ^ Gberie, pp. 106 and 88

- ^ Zack-Williams, Tunde (2011). When the State Fails: Studies on Intervention in the Sierra Leone Civil State of war. Pluto Printing. p. 24. ISBN9781849646246.

- ^ a b Gberie, p. 93

- ^ Gberie, p. 94

- ^ Abdullah, p. 96

- ^ a b Gberie, p. 95

- ^ "Elections in Sierra Leone". African Elections Database. 17 September 2007. Retrieved 24 December 2010.

- ^ Abdullah, p. 144

- ^ Abdullah, p. 206

- ^ "Chronology". Paying the toll: The Sierra Leone peace procedure. Conciliation Resources. September 2000.

- ^ Abdullah, pp. 118–19

- ^ Allie, Joe (2005). "The Kamajor Militia in Sierra Leone: Liberators or Nihilists?". In Francis, David J. (ed.). Civil Militia: Africa's Intractable Security Menace?. Burlington, VT: Ashgate. p. 59.

- ^ Abdullah, p. 148

- ^ Gberie, p. 107

- ^ Gberie, p. 108

- ^ Abdullah, p. 156

- ^ "The AFRC remained a pariah junta, shunned by every government in the world." Abdullah, p. 156

- ^ Abdullah, p. 158

- ^ Gberie, p. 112

- ^ "Shocking State of war Crimes in Sierra Leone New Testimonies on Mutilation, Rape of Civilians". Human Rights Spotter. 24 June 1999.

- ^ Abdullah, p. 161

- ^ Abdullah, p. 223

- ^ Gberie, p. 121

- ^ Ero, Comfort; Sidhu, Waheguru Pal Singh; Toure, Augustine (September 2001). "Toward a Pax West Africana: Building Peace in a Troubled Sub-region" (PDF). International Peace Academy: twoscore – via International Peace Institute.

- ^ Abdullah, p. 212

- ^ Abdullah, p.199

- ^ a b Abdullah, p. 213

- ^ Abdullah, p.166

- ^ Gberie, p. 163

- ^ Gberie, p. 187

- ^ a b Wood, Larry J.; Reese, Colonel Timothy R. (2008). "Armed services Interventions in Sierra Leone: Lessons From a Failed State" (PDF). The Long War Series Occasional Paper. 28. Combat Studies Institute Press: 117 – via Defense Technical Information Center.

- ^ Gberie, p. 164

- ^ a b Malan, Marker, Phenyo Rakate and Angela MacIntyre (January 2002). "Chapter Four: The 'New' UNAMSIL: Strength and Limerick". Peacekeeping in Sierra Leone: UNAMSIL Hits the Abode Directly. Pretoria, Due south Africa: Institute for Security Studies. Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 29 Dec 2010.

{{cite spider web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b McGreal (21 September 2000). "Indian troop recollect shifts onus to Nato". The Guardian . Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ Malan, Mark, Phenyo Rakate and Angela MacIntyre (January 2002). "Affiliate Three: UNAMSIL's Troubled Debut". Peacekeeping in Sierra Leone: UNAMSIL Hits the Habitation Straight. Pretoria, South Africa: Institute for Security Studies. Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 29 December 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors listing (link) - ^ Gberie, p. 189

- ^ "SMOTR: Mi-24 in Sierra Leone! (English subtitles)". YouTube. Retrieved 21 January 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Operation Khukri". UN Ops involving the Indian Air Forcefulness. Vayu-sena.tripod.com. Retrieved xiii July 2012.

- ^ "Peacekeeping in Sierra Leone". India-rakshak.com. Archived from the original on 29 Baronial 2012. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- ^ "IAF 2000 Contingent to UNAMSIL". UN Mission. Official Website of the Indian Air Force. Retrieved nineteen July 2012.

- ^ Gberie, p. 173

- ^ Gberie, p. 176

- ^ Abdullah, p. 221

- ^ Gberie, p. 172

- ^ Gberie, p. 170

- ^ Abdullah, p. 229

- ^ Hirsch, p. 31

- ^ "Observing The 2002 Sierra Leone Elections" (PDF). The Carter Center: 54. May 2003.

- ^ a b Shah, Anup. "Sierra Leone". Global Issues . Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ^ "Sierra Leone" Archived 2 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine. 2001 Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor. Bureau of International Labor Affairs, U.S. Department of Labor (2002)

- ^ Gberie, p. 125

- ^ Sierra Leone: getting abroad with murder, mutilation, rape, Radio Netherlands Archives, Jan 25, 2000

- ^ "Getting Away with Murder, Mutilation, Rape: New Testimony from Sierra Leone". Man Rights Scout. July 1999. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- ^ Junger, Sebastian (8 Dec 2006). "THE TERROR OF SIERRA LEONE". Vanity Fair: Hive.

- ^ "Sierra Leone – Human Rights". Bella Online . Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ^ Innocence Lost, Radio Netherlands Archives, February xvi, 2000

- ^ The Memories should exist their penalisation, Radio Netherlands Archives, Jan 12, 2000

- ^ Oosterveld 2013, p. 235. sfn error: no target: CITEREFOosterveld2013 (help)

- ^ Wood 2013, p. 145. sfn error: no target: CITEREFWood2013 (aid)

- ^ Meyersfeld 2012, p. 164. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMeyersfeld2012 (help)

- ^ Denov 2010, p. 109.

- ^ Mustapha 2003, p. 42. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMustapha2003 (help)

- ^ Kennedy & Waldman 2014, pp. 215–216. sfn error: no target: CITEREFKennedyWaldman2014 (help)

- ^ Decker et al. 2009, p. 65. sfn mistake: no target: CITEREFDeckerOramGuptaSilverman2009 (help)

- ^ Martin 2009, p. l. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMartin2009 (help)

- ^ Simpson 2013. sfn fault: no target: CITEREFSimpson2013 (help)

- ^ Reis 2002, pp. 17–eighteen. sfn error: no target: CITEREFReis2002 (aid)

- ^ Cohen 2013, p. 397. sfn error: no target: CITEREFCohen2013 (help)

- ^ "YouTube". YouTube. Retrieved 19 November 2021. [ dead YouTube link ]

- ^ Bell, 2005

- ^ "UNAMSIL: United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone". Un.org . Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- ^ "Sierra Leone: Submission to the Universal Periodic Review of the Un Human being Rights Council", International Middle for Transitional Justice (ICTJ)

- ^ "Challenging the Conventional: Tin Truth Commissions Strengthen Peace Processes?", International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ)

- ^ Brittain, Victoria (2 March 2000). "Return of Sierra Leone's lost generation". the Guardian . Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- ^ a b c Kuiter, Bart (July–August 2001). "Postal service State of war Reconstruction in Sierra Leone" (PDF). Courier ACP-EU: 76–77.

- ^ "Twenty-fifth report of the Secretarial assistant-General on the United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone" (PDF). Unipsil.unmissions.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2014. Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- ^ Lykke, A.M. and Due, M.One thousand. and Kristensen, Chiliad. and Nielsen, I. (2004). The Sahel. Proceedings of the 16th Danish Sahel Workshop. Dept. of Systematic Botany, Institute of Biological Sciences, Aarhus University. pp. volume v folio 6. ISBN978-87-87600-38-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Mysterious Death of a Fugitive". The Perspective. The Perspective (Atlanta, Georgia, United states). 7 May 2003. Retrieved xviii January 2008.

- ^ Crane, David One thousand. (three March 2003). "Instance NO. SCSL – 03 – I, The Special Court for Sierra Leone". Freetown, Sierra Leone: United Nations and the Authorities of Sierra Leone. Archived from the original on 19 Nov 2007. Retrieved 18 January 2008.

- ^ "Foday Sankoh". The Economist. 7 August 2003. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ^ "Sierra Leone rebel leader dies". BBC News. 30 July 2003. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ^ "Guilty Verdicts in the Trial of the AFRC Defendant" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2008. (104 KiB), press release from the Special Court for Sierra Leone, xx June 2007; "Sierra Leone Convicts 3 of War Crimes", Associated Press, 20 June 2007 (hosted by The Washington Post); "Commencement Southward Leone war crimes verdicts", BBC News, 20 June 2010

- ^ "Sierra Leone Refugee All Stars: A Documentary Film". Refugeeallstars.org . Retrieved 24 December 2010.

- ^ Boyd, Brian (16 March 2007). "Taking the rap for bloody bling". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 19 July 2021. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- ^ "Artist – Kanye West". Grammy.com. Archived from the original on 8 December 2018. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- ^ "2006 BMI London Awards". BMI. iii October 2006. Archived from the original on 13 March 2016. Retrieved 21 Jan 2019.

- ^ "More at IMDbPro » Blood Diamond (2006)". IMDb . Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ Burr, Ty (xvi September 2005). "Provocative 'State of war' Skillfully Takes Aim". The Boston Globe: D1.

- ^ Kamara, 2008, pp. 7–viii.

- ^ Academy of Florence (Italy), Conflict management course, thesis of comparison betwixt recruitment of child soldiers and recruitment of children of Camorra in Naples. Title Child soldiers in the Globalized North? Organized crime and youth in Naples (thesis by Alma Rondanini, Prof. Giovanni Scotto – A.A. 2012/2013)

- ^ University La Bicocca of Milan (Italy), Degree in Science Education, thesis based on the analysis of Male parent Berton's educational model and its role in mail service-conflict contexts, title A laboratory for the rehabilitation of onetime kid soldiers in Sierra Leone (thesis by Sara Pauselli, Prof. Mariangela Giusti – A.A. 2012/2013)

- ^ "Jonathan Torgovnik'southward 'Daughter Soldier,' Life Later on War in Sierra Leone". eighteen June 2014. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

Sources [edit]

- Abdullah, Ibrahim (2004). Betwixt Democracy and Terror: The Sierra Leone Ceremonious State of war. Dakar: Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa.

- Adebajo, Adekeye (2002). Republic of liberia's Civil War: Nigeria, ECOMOG, and Regional Security in W Africa. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- AFROL Groundwork: The civil state of war in Sierra Leone

- Bell, Udy (December 2005). "Sierra Leone: Edifice on a Difficult-Won Peace". UN Chronicle. Archived from the original on 22 Oct 2012. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- Pugh, Michael; Cooper, Niel; Goodhand, Jonathan (2004). War Economies in a Regional Context: Challenges of Transformation. Bedrock, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Gberie, Lansana (2005). A Muddied War in West Africa: the RUF and the Destruction of Sierra Leone. Bloomington, IN: Indiana Upward.

- Hirsch, John Fifty. (2000). Sierra Leone: Diamonds and the Struggle for Commonwealth. Bedrock, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Kamara, Mariatu with Susan McClelland (2008). The Bite of the Mango. Buffalo, NY: Annick Press.

- Keen, David (2005). Conflict & Collusion in Sierra Leone. Oxford: James Currey.

- Koroma, Abdul Karim (2004). Crisis and Intervention in Sierra Leone 1997–2003. Freetown and London: Andromeda Publications.

- Richards, Paul (1996). Fighting for the Rainforest: War, Youth and Resources in Sierra Leone. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

- U.Due south. Dept. of Country Groundwork Note: Sierra Leone

- Forest, Larry J. & Colonel Timothy R. Reese. (May 2008). "Military machine Interventions in Sierra Leone: Lessons From a Failed Land" (PDF). Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: Combat Studies Establish Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 May 2010.

Further reading [edit]

Books [edit]

- Beah, Ishmael (2007). A Long Manner Gone: Memoirs of a Boy Soldier. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Bergner, Daniel (2003). In the State of Magic Soldiers: a Story of White and Black in Africa. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Campbell, Greg (2004). Blood Diamonds: Tracing the Deadly Path of the World'south Most Precious Stones. Bedrock: Westview.

- Denov, Myriam Southward (2010). Child soldiers: Sierra Leone's Revolutionary United Forepart. New York: Cambridge University Printing.

- Dorman, Andrew K (2009). Blair's Successful War: British Military Intervention in Sierra Leone. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

- Mustapha, Marda; Bangura, Joseph J. (2010). Sierra Leone Beyond the Lomé Peace Accord. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mutwol, Julius (2009). Peace agreements and Civil Wars in Africa: Insurgent Motivations, Country Responses, and Third-Party Peacemaking in Liberia, Rwanda, and Sierra Leone. Amherst, NY: Cambria Press.

- Olonisakin, Funmi (2008). Peacekeeping in Sierra Leone. Bedrock, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Özerdem, Alpaslan (2008). Postal service-War Recovery: Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Sesay, Amadu; et al. (2009). Post-War Regimes and Country Reconstruction in Liberia and Sierra Leone. Dakar: Quango for the Evolution of Social Science Research in Africa.

Periodical articles [edit]

- Azam, Jean-Paul (2006). "On Thugs and Heroes: Why Warlords Victimize Their Own Civilians" (PDF). Economics of Governance. 7 (1): 53–73. doi:x.1007/s10101-004-0090-x. S2CID 44033547.

- Heupel, Monika & Bernhard Zang (2010). "On the Transformation of Warfare: a Plausibility Probe of the New War Thesis". Journal of International Relations and Evolution. 13 (1): 26–58. doi:ten.1057/jird.2009.31. S2CID 55091039.

- Jalloh, S. Balimo (2001). "Conflicts, Resources and Social Instability in Subsahara Africa – The Sierra Leone Case". Internationales Afrika-Forum. Frg. 37 (2): 166–fourscore.

- Gberie, Lansana (1998). War and state plummet: The instance of Sierra Leone (M.A. thesis). Wilfrid Laurier University.

- Lujala, Paivi (2005). "A Diamond Curse?: Ceremonious War and a Lootable Resource". Journal of Conflict Resolution. 49 (4): 538–562. doi:10.1177/0022002705277548. S2CID 154150846.

- Zack-Williams, Alfred B. (1999). "Sierra Leone: the Political Economy of Ceremonious War, 1991–98". Third World Quarterly. 20 (1): 143–62. doi:ten.1080/01436599913965.

External links [edit]

- International Center for Transitional Justice, Sierra Leone

- Text of all peace accords for Sierra Leone

- Life does not lose its value, Documentary by Wilma Massucco

- Cry Freetown, Interview to Sorious Samura

- Postcards from Hell

- A Long Way Gone by Ishmael Beah

- Global Security

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sierra_Leone_Civil_War

0 Response to "What Were the Rebels Fighting Agains in Sierra Leone"

Post a Comment